How Should We Explain Miracles?

Do we need to assume anything supernatural to understand why claims for the reality of miracles appear in human history

1. What a miracle would mean scientifically

If the laws of nature are truly universal and unchanging, then a genuine miracle -- in the traditional sense of suspending or overriding those laws -- would be something more than just an improbable event. It would be an impossible event under known physics.

Example: water turning into wine without chemical processing would violate conservation of mass-energy and chemistry.

If this truly occurred, it would mean our current understanding of physics is incomplete or wrong.

This is very different from a highly improbable event, which still obeys the laws but happens to be rare (like someone surviving a plane crash unharmed).

2. History is full of “miracles” that shrink under investigation

When events are far in the past -- especially in pre-scientific eras -- the explanations we get are filtered through:

Low-quality evidence (oral tradition, hearsay, copying errors).

Cultural storytelling (embellishment for moral, political, or religious purposes).

Misinterpretation of natural phenomena (eclipses, comets, disease outbreaks) by people without the conceptual tools to explain them naturally.

In other words: what looked like a suspension of natural laws was often just a gap in understanding plus a strong human desire to find meaning or authority.

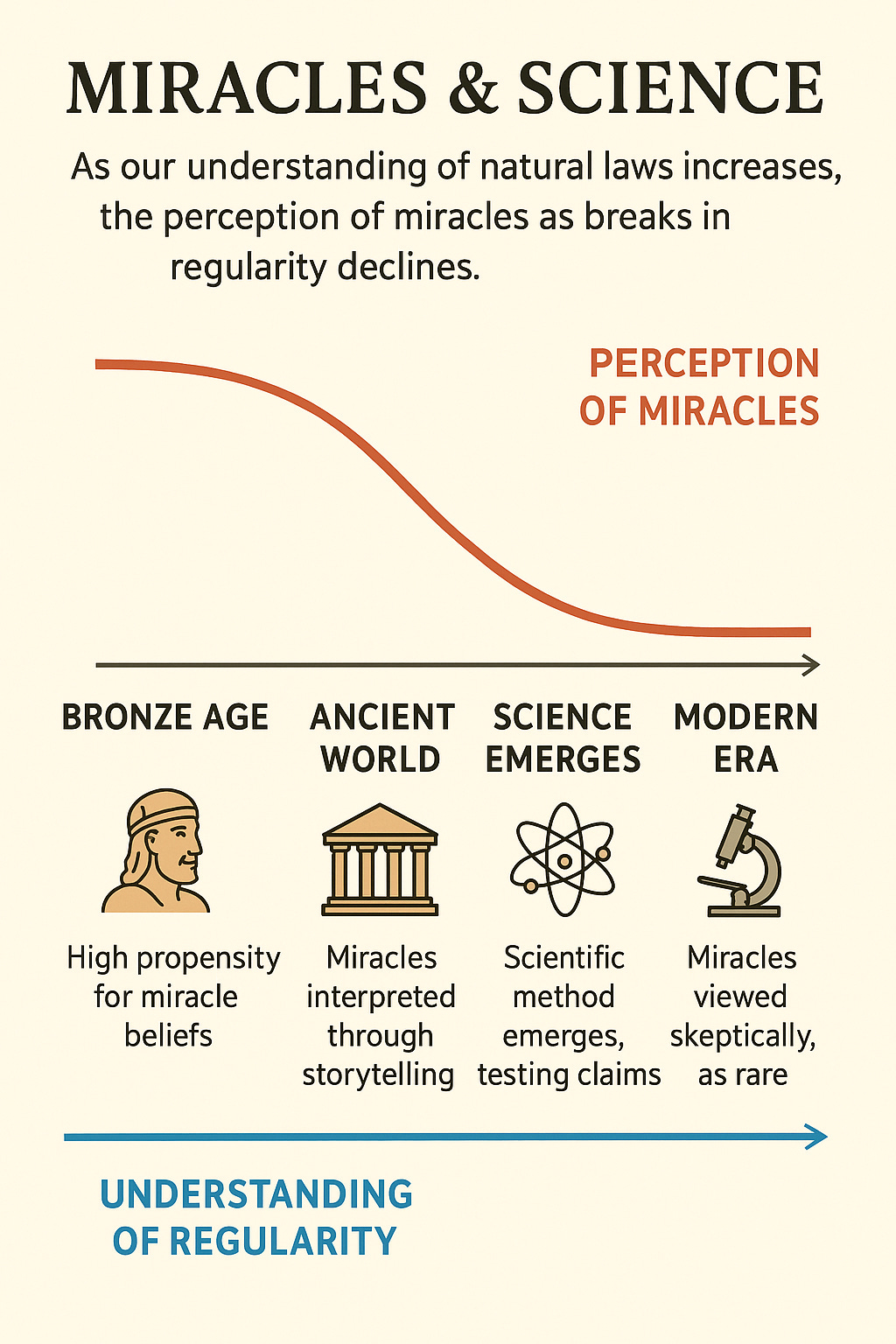

3. Why “miracles” were more common in the Bronze Age

The Bronze Age had:

No systematic scientific method -- so no way to test claims objectively.

High dependence on authority -- religious or political leaders whose power was reinforced by miracle stories.

A myth-making culture -- events were embedded in narratives that served social cohesion, moral teaching, or propaganda.

Once you combine low skepticism, limited literacy, and the social power of storytelling, miracle reports become culturally inevitable.

4. Entropy, regularity, and miracles

From the entropy–regularity framework:

Regularity is the backdrop -- the “riverbanks” -- that shapes every event.

Entropy means improbable arrangements happen, but within the rules.

A true miracle would be like the river suddenly flowing uphill with no external force -- a break in the regularity itself.

So when we hear ancient miracle claims, we can see them as perceived breaks in the regularity, likely born from misunderstanding or storytelling, rather than actual violations of physical law.

Bottom line:

If a miracle really happened, it would be the most valuable scientific discovery in history -- a clue to deeper laws. But so far, every well-documented event either fits the known laws or is too poorly evidenced to test. The Bronze Age miracle stories tell us more about human psychology and culture than about the actual structure of the cosmos.

Miracles: The Bronze Age's Greatest Hits

A “miracle,” so we’re told, is a violation of the laws of nature -- a special dispensation granted by the celestial bureaucracy to remind us who’s in charge. The very premise is revealing: the universe, ordinarily governed by consistent, testable rules, must occasionally be interrupted, like a film reel with a scratch, so that the divine can make a cameo.

Now, to the scientifically literate mind, this is odd. The laws of nature are not municipal by-laws, written up in some celestial clerk’s office and subject to waiver. They are descriptions of how the world works -- universally, relentlessly, without a single recorded breach. Were such a breach to occur, it would not be a “miracle” in the Sunday-school sense; it would be the most important data point in the history of science, demanding not worship but laboratory replication.

So why, then, are the alleged glory days of miracle-working always lodged firmly in the pre-literate, pre-scientific Bronze Age? Why do seas part for goatherds, but stubbornly refuse to part for BBC documentary crews? Why do the dead rise when only credulous villagers are present, but never under controlled observation? The answer is painfully obvious: in the absence of any method for verification, any story -- however implausible -- could be believed, especially if it came from a priest or king whose authority depended on it.

Eclipses became divine temper tantrums. Diseases were the punishment of gods, and their remission the reward for piety. A gust of wind at the right time could launch a religion. And when eyewitnesses are few, illiterate, and inclined to please their leaders, the miraculous is in infinite supply.

Fast forward to today: the scientific method emerges, instruments are invented, skepticism becomes a civic virtue -- and lo, the miracle supply dries up. The modern “miracle” is a weeping statue, a face on a piece of toast, or a medical recovery that can be filed neatly under “statistical outlier.”

Miracles, in short, are the fossil record of our ignorance. They flourish where understanding is absent, and vanish when the light of inquiry is turned on. The real miracle -- if one is needed -- is that we ever managed to crawl out of that intellectual darkness at all.

In conclusion, a miracle is simply the name we give to a gap in our understanding, usually filled with whatever superstition is most fashionable at the time. That’s why they abound in the credulous fog of the Bronze Age and vanish in the glare of modern inquiry. Show me a god who can turn water into wine under double-blind conditions, and I’ll show you the Nobel committee warming up their pens -- until then, it’s all hearsay and holy gossip.